From lab to life

by Syl Kacapyr

Biomedical engineers bring their research to the world.

Inside David Putnam’s garage was a captivating blend of organized chaos, or as he described it, “an awful mess.” Amidst the typical sight of half-empty paint cans and stacked cardboard boxes, an array of glass beakers, test tubes and ovens occupied a makeshift science lab.

Putnam, the Samuel B. Eckert Professor in Cornell’s Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, couldn’t sit idle during the 2020 pandemic lockdown. Instead, he accepted a challenge from one of his surgeon colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine, Dr. Jason Spector: To invent a safe, dissolvable, surgical barrier that could be used to protect organs from suture needles.

“I went to my garage and I was figuring out what temperature and time and humidity to bake these different materials, all of which were already approved by the FDA,” said Putnam, who is also associate dean for innovation and entrepreneurship at Cornell Engineering. “I couldn’t work in my lab during the pandemic shutdown, so I used the time to work my way through the matrix of different conditions.”

Putnam eventually found success with a precise concoction that yielded a material strong enough to withstand a needle while capable of dissolving in the human body. Today, the surgical barrier is undergoing pre-clinical trials and Putnam hopes it will receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration sometime next year.

The entrepreneurial spirit of Putnam, who has co-founded three companies based on his Cornell research, is embedded throughout the Meinig School thanks to a growing slew of programs designed to give faculty and students the resources they need to validate an idea, develop a business plan, build a prototype, and bring research from bench to bedside.

In Putnam’s opinion, if a device can be made in a lab, it can likely be made for the world.

“My mindset is that when we do research on behalf of the public and with taxpayers’ money, we have a moral obligation to bring that research forward commercially,” Putnam said. “Without products going to the public it’s a disservice because they’re paying for that technology, they’re paying for those advances.”

Turning labs into launchpads

Ilana Brito, associate professor of biomedical engineering, is no stranger to adventurous quests in the name of science. Research into how genes are spread between human microbiomes brought her to the Pacific island of Fiji, and more recent projects have her collaborating with scientists from India, Nepal, Guatemala, Mexico and Brazil.

But the terrain Brito currently finds herself in is a new type of expedition, one into the realm of research commercialization.

“I’m new to this world,” humbly confessed Brito, who is exploring commercial opportunities for her research through the Entrepreneurship Fellowship, a new program at Cornell Engineering that encourages faculty to spend their sabbatical identifying promising business directions for their science.

“My group is mainly interested in drug development and potentially diagnostics as well,” Brito said. “We have some platform technologies, but to make them truly valuable, we need to have early successes that we can point to. Then you have something that’s really valuable for a business startup opportunity, because it has areas of growth.”

As part of the Entrepreneurship Fellowship, Brito has been meeting with alumni working in relevant fields, including from the pharmaceutical industry, which is changing how she thinks about research in her lab.

“It’s helped me choose projects for students that have that type of commercial runway,” Brito said. “More and more students these days are interested in industry and entrepreneurship, so this potentially gives them opportunities to get their feet wet with research that might turn into something of their own.”

With commercialization now on her radar, Brito joins the Meinig School’s growing roster of faculty and students with an entrepreneurial mindset. In the school’s brief history—the Department of Biomedical Engineering was established in 2004 and the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering was instituted in 2015—its faculty have negotiated 26 license agreements for their intellectual properties, and the school boasts more fellows of the National Academy of Inventors—David Putnam, James Antaki, Yadong Wang, and David Fischell—than any other at Cornell.

Entrepreneurship has been a part of the Meinig School’s culture since its founding, with many of its earliest faculty members seeking to commercialize their work. One of those researchers is Larry Bonassar, the Daljit S. and Elaine Sarkaria Professor in Biomedical Engineering.

“A key part of the mission of any university, particularly a Land Grant university, is not only to generate new knowledge, but to use this knowledge for the betterment of humanity and the world,” Bonassar said. “In the field of biomedical technology, bringing our inventions to the world effectively requires partnership with industry and commercialization.”

Some of Bonassar’s earliest work at Cornell focused on tissue engineering and bioprinting. He later co-founded 3DBioTherapeutics with Daniel Cohen ’04, M.S. ’07, Ph.D. ’10., and last year in a first-of-its-kind clinical trial, a human received a 3D-bioprinted ear implant grown from the patient’s own living cells.

Bonassar also has partnered with regenerative medicine company Histogenics on a novel cell therapy to repair knee cartilage defects, and Italian pharmaceutical company Fidia Farmaceutici on hyaluronic acid products to treat osteoarthritis and herniated intervertebral discs.

“I find working with scientists in industry to be invigorating,” Bonassar said. “On multiple occasions, I have collaborated with industrial scientists who wanted to know more about their products and in the process of exploring this space, we discovered principles that underlie not only their product, but whole classes of products and therapies. This has been some of my most impactful work.”

Other notable startups from the Meinig School’s early faculty include Hesperos, a company based on the body-on-a-chip research from professor emeritus Michael Shuler, and two companies co-founded by Putnam: ProVis Medical, focused on medical devices; and Versatope Therapeutics, which is developing a universal vaccine against influenza with the potential to be longer lasting and more effective than traditional seasonal vaccines.

“I think that it’s no coincidence that this culture of entrepreneurship has carried through and that even our younger faculty are so successful in starting companies and partnering with industry,” Bonassar said.

The science of derisking business

Entire communities of bacteria, hundreds of species, are crawling around your gut. These microbes play an important role in human health and biology, but exactly how they interact with each other and their host has remained poorly understood.

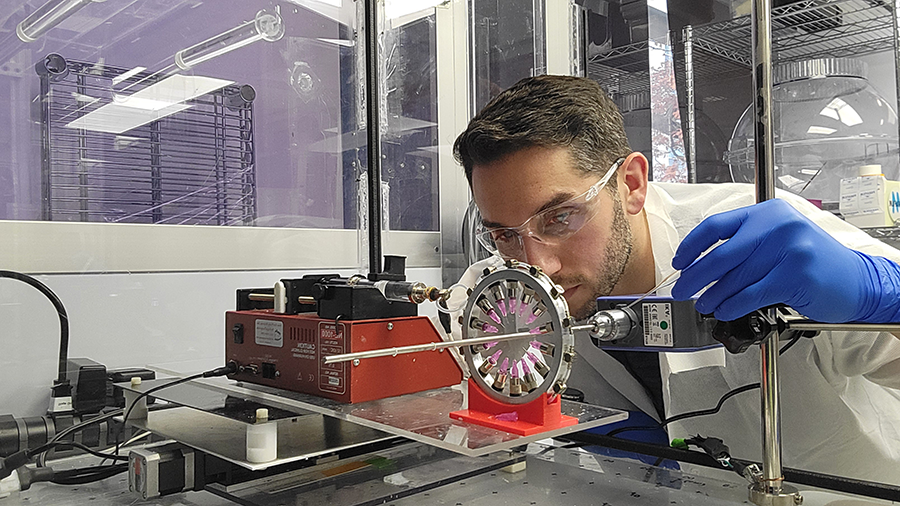

A new microbiome mapping technology is emerging from Kanvas Biosciences, a startup formed by Cornell biomedical engineers that aims to revolutionize microbial research and infectious disease diagnostics using a combination of imaging techniques and machine learning.

The company—co-founded by Meinig School associate professor Iwijn De Vlaminck and Hao Shi, M.Eng. ’18, Ph.D. ’20 —announced $12 million in pre-series A funding in June, which will be used to further advance the company’s transcriptomics platform and to discover new technologies.

“It’s been rewarding and inspiring to see our research lead to a new company,” said De Vlaminck. “What’s even better is to see many talented scientists and engineers come together to build the technology further and to explore new applications.”

Derisking a business idea into a stable and promising venture requires experiments, prototyping or other proofs of concept. De Vlaminck and Shi conducted initial research using seed funds from the Kavli Institute at Cornell and the National Institutes of Health. But not all research projects can attract such funding. That’s why Putnam is developing what he calls the CoEfficient Initiative – a college-wide program that aims to match unmet commercial needs with technical solutions, validate the market potential of those solutions using committees of industry-based alumni, and provide seed funding to pursue the solutions.

“What experiments do you need to take an idea from a high-risk, low-value proposition to something we know is going to work? If the experiments cost $15,000, then the initiative’s funds can provide that. If an idea works, what’s the next experiment and how can the college support that?” said Putnam. “If an idea still works, then we’ve got an investable high-value, low-risk opportunity.”

One result of the initiative, said Putnam, is that the quality of companies entering Cornell’s business incubator programs will increase, as will positive outcomes like that of Kanvas Biosciences. The company received its recent round of venture funding less than a year after graduating from Cornell’s Center for Life Sciences Ventures business incubator, which has several Meinig School Advisory Council members serving as consultants.

“When investors evaluate a startup for funding, they generally first assess the size of the opportunity and how well the proposed technology addresses the requirements for a commercially viable solution,” said Beckie Robertson ‘82, founder and general partner at Versant Ventures who advises both the Meinig School and the Center for Life Sciences Ventures. “Once that box is checked, in order to attract funding for your technology, you need to have in hand some objective proof of concept data to give the investor a reason to believe. Of course, many risks will still remain so it is equally important to clearly identify and articulate what the next major derisking milestone is that must be achieved to unlock future capital.”

Another program Meinig School faculty are using to derisk research is the Cornell Engineering Sprout Awards, a new funding initiative designed to fill the financial gap between seed projects and successful sponsorship by an external agency.

Biomedical professors Shaoyi Jiang and Chris Schaffer are using a Sprout Award to develop a new method of in-vivo delivery of mRNAs into the brain. A second award partnered De Vlaminck, associate professors Nozomi Nishimura and Nelly Andarawis-Puri and other researchers to explore new treatments for tendon injuries.

A new generation of biomedical entrepreneurs

He didn’t know it at first, but Diego Rey, Ph.D. ’10, had a $425 million idea.

While studying biomedical engineering at Cornell, Rey and two fellow students formed a startup for a diagnostic technology to detect drug-resistant bacteria. The trio took advantage of several resources at Cornell, including an Entrepreneurship for Scientists and Engineers course, an entrepreneurship internship program, a startup bootcamp, and the Center for Technology Licensing. These resources kickstarted a journey that eventually led the company, GeneWEAVE BioSciences, to land a $425 million deal with an international health care company Roche.

“My fundamental training at Cornell still helps me to this day,” said Rey, who is now co-founder and chief scientific officer at Endpoint Health, a precision immunology therapeutics company. Rey also sits on the Meinig School’s Advisory Council, which has been discussing entrepreneurship as a key topic. “The Meinig School is an ideal place for entrepreneurs because biomedical engineering combines science, medicine and engineering, so it’s a conduit through which to translate science into practice in medicine.”

Cornell Engineering and the Meinig School have continued to grow a roster of programs aimed at entrepreneurship education and encouraging students and postdocs to consider the commercial side of their science, just as Rey did (see callout for recent examples).

The Meinig School’s own training programs have focused on clinical immersion and its strong relationship with Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. Through the Ph.D. Summer Immersion Term, doctoral students learn to identify the technological needs of clinicians by attending surgeries and participating in clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine and its affiliated New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Undergraduates, too, can see the role engineers play in clinical medicine through the new Shuler Scholars program funded by Beckie Robertson ’82 and Neil L. Robertson ’82, who wanted undergraduates to experience entrepreneurship by seeing clinical needs at Weill Cornell Medicine before bringing that perspective into their senior design class.

“I like everything within the clinical environment—creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship—and I knew this was the academic environment that would best assist me in successfully transforming from a student to a professional,” said Bayan Alturkestani, M.Eng. ’20, who enrolled in the Meinig School’s M.Eng. Clinical Preceptorship program and observed more than 55 hours of surgeries at Guthrie Hospital in Sayre, Pennsylvania. Alturkestani has joined a long list of M.Eng. alumni entrepreneurs and is now the president and founder of Conan MedTech, a startup focused on real-time concussion detection.

Since launching the Clinical Preceptorship program, the Meinig School has also introduced an M.D.-M.Eng. degree with Weill Cornell Medicine. And a college-wide clinical translation grant is being developed for postdoctoral researchers interested in areas like osteoarthritis, women’s health, surgical devices and neurology.

“I believe biomedical engineers need to have a present and deep experience in medicine,” Alturkestani said. “I liked having a chance to talk with and ask physicians about the unmet healthcare needs their patients face, as well as the problems they experience inside the operating room with old, new, and limited or lack of technology.”

Alturkestani’s experience emphasizes the value of an intimate connection between engineering, medicine and business, and that the journey connecting them is no solitary pursuit. With each collaboration, each clinical immersion and each business venture, the Meinig School is catalyzing a culture in which faculty and students are empowered to bring their science directly to the world.

As for Putnam, he still enjoys engineering in his garage. But even more exciting to him is the prospect of seeing his inventions help people. After more than a decade of research and development, the universal vaccine being produced by his startup Versatope Therapeutics will soon be entering human clinical trials.

Said Putnam: “If all goes well, this could change how vaccination against influenza, and hopefully other pathogens, are done forever.”

Proof-of-concept: entrepreneurship education in action on campus:

- Ave Kludze ’23 received mentorship from the Cornell Engineering Entrepreneurs-in-Residence program before landing an internship at biotech startup GRO Biosciences through Cornell’s Kessler Fellows program;

- A group of biomedical undergraduates won a Cornell Engineering Innovation Competition award, which included a monetary prize, for their invention of MyUD, a smart contraceptive device;

- Nicole Diamantides, Ph.D. ’19, now a senior scientist at IVIVA Medical, used Cornell Engineering’s Commercialization Fellowship program to explore the market potential for a collagen bioink. The program provided guidance on customer discovery, intellectual property management, supply chains and team management;

- Postdoctoral fellow Anthony D’Amato is examining the commercial potential of biomaterials that aid in the generation of blood vessels through the BioEntrepreneurship Initiative, which pairs scientists with business students, and the Ignite Fellowship for New Ventures, which funds and trains Ph.D. and master’s holders to start technology ventures;

- Amanda Bares, Ph.D. ‘16, now associate director, tissue biomarkers at Invicro, was among the first cohort of Cornell Engineering’s Commercialization Fellows and explored the market potential for a first-of-its-kind microscope that can image fluorescent cells in living tissue using 48 channels of color information.